Late 1800’s Ancestors :

Mainly Sri-Lanka

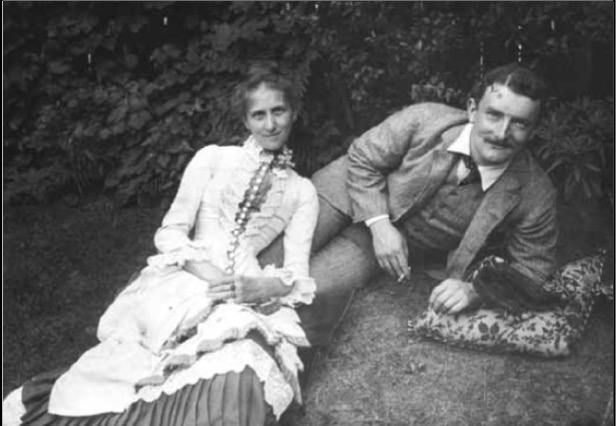

Florence Letitia Fuller

Born: 12 Sept 1853

Sydenham, Kent

Died: 20 Jan 1909

Buckinghamshire, England

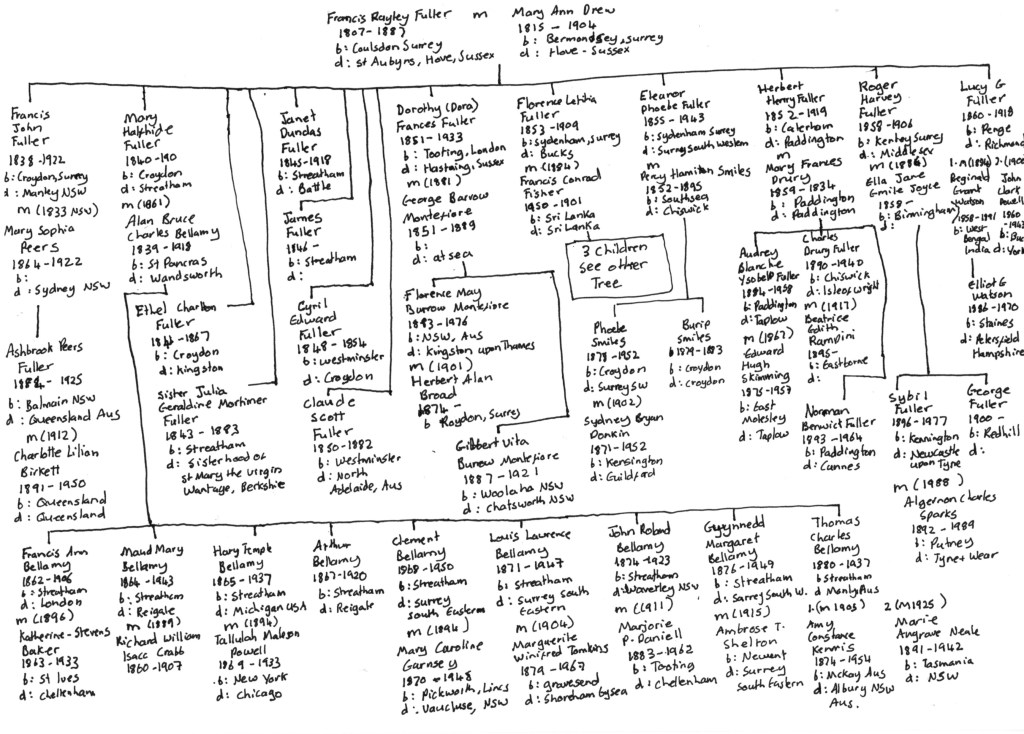

Florence Letitia Fuller was born in Sydenham in Kent near Crystal Palace. Her father Francis Raleigh Fuller worked for 25 years as the Surveyor for Southern Railways. He was also involved in raising finance and organising the great exhibition with his father-in-law.. At the time of her birth he was spending 4 years working as a director of Crystal Palace.

Her mother Mary-anne Drew was from Bermondsey, South London whose father was an eminent Lawyer.

Her sister Dora gives an account of how they lived at Kenley house, near Crawley. They were brought up mainly by nannies and would visit their parents in the evenings.

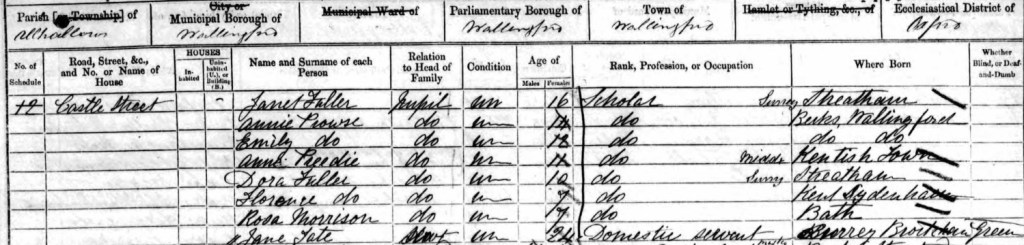

Florence was one of a large family of 14 siblings. In 1861 aged 7 she was at a small school boarding house of just 8 pupils at 12 Castle street in Wallingford, Oxfordshire. She was with her sisters Dora and Janet.

According to an account by her sister Dora they next went to a school in Brighton and were taught both French and German to a good standard. Dora gives a good account also about how the wider circle of people her father was involved with provided an education in it’s own right.

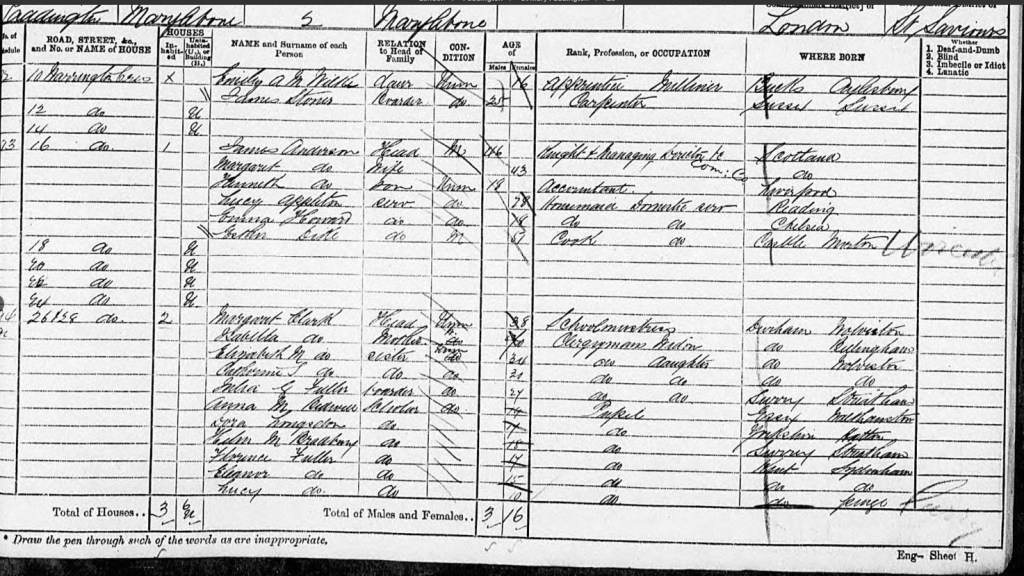

In 1871 aged 17 she was at another small girls boarding school in Paddington. Her older sister Julia (aged 21) is there and her two younger sisters Eleanor and Lucy.

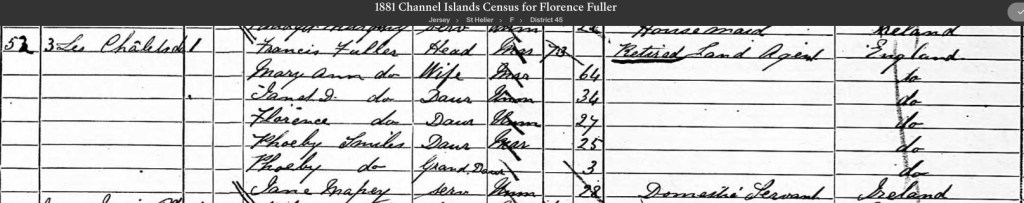

By 1881 she was with her parents in St Hellier, Jersey at the age of 28. This was possibly a holiday as there is no evidence that they lived there for any length of time. Florence’s parents then moved to Hove in 1882 and Florence probably moved with them to 63 St Aubyn’s Road.

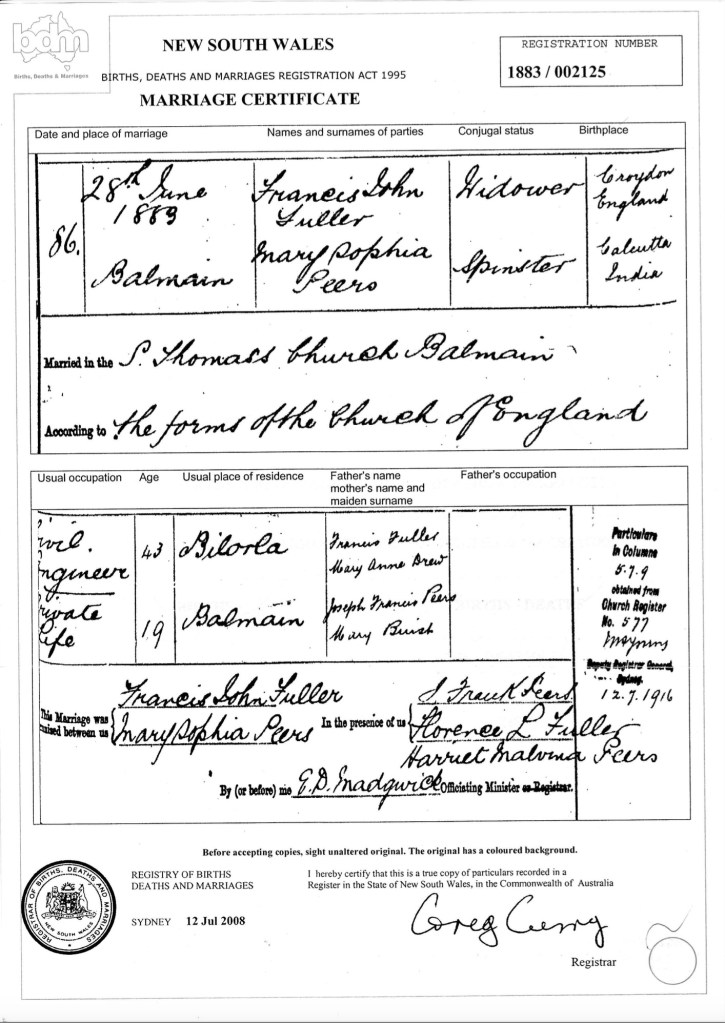

In June of 1883 Florence was in Australia because she was a witness to her brother Francis John’s second marriage. She must have returned home fairly quickly because she was married herself in England the following year.

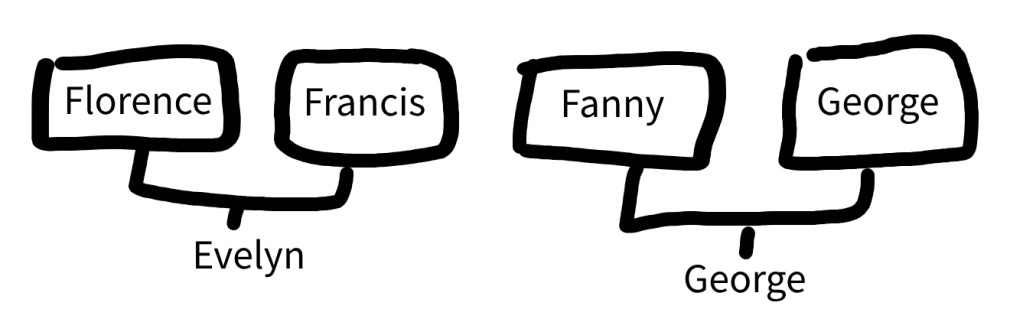

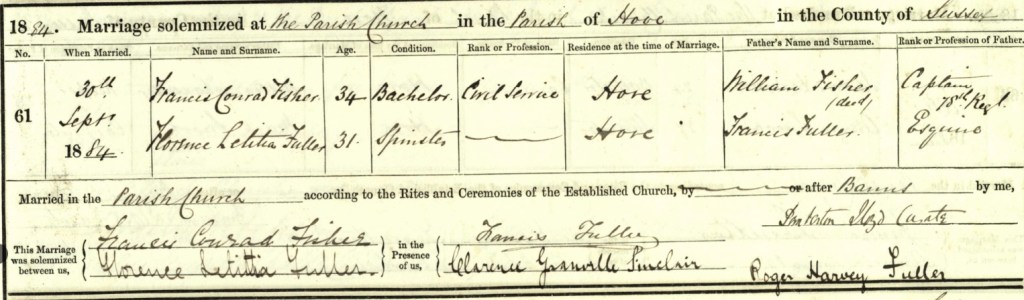

At some point in 1883/84 that Florence met her husband – I wonder if she stopped in Sri Lanka on her way to Australia or on her way back. They were married at in Hove, Sussex from her parents home. Then the couple headed out to Sri Lanka where they had three children: Conrad, Irene and Evelyn.

Sadly Florence’s husband died unexpectedly and tragically when she was 47. His probate shows he did not leave much for Florence so she may have struggled somewhat.

She returned to live in Bedford in England. Her daughter Irene is recorded attending Bedford high school from 1901. Another record shows Irene as a bridesmaid at the wedding of cousin Phoebe Smiles.

By 1909 Florence is living at Woodbine cottage in Wavendon, Bucks. This was the birth place of her father-in-law so I imagine it was a Fisher family residence that she was living in. Florence died there in 1909 aged 55. She died of “Sprue” this can be a tropical illness where you waste away or it could have been cealiac diesease. It seems like a friend M. Crofts was with her when she died.

Florence’s closest sister in age was Dora Montefiore nee Fuller who was a famous women’s rights activist. Dora named one of her daughters Florence so perhaps they were close. In her will Dora left everything to her daughter Florence except a fur coat and a bust of her grandmother Sarah Sayer Hitchins. She left these to Florence’s daughter Evelyn who was also a widow… so it seems they had some sort of relationship.

Her other close sister in age Eleanor was also very kind to Florence’s daughter Evelyn when she was widowed later.

The couples son Conrad Fisher worked on tea plantations in Sri Lanka. He had one son also a Conrad who died in an accident in the Uk after his parents retired back to England.

Irene and Evelyn both also married in Sri Lanka. It seems likely that after their mother died they went out there to live with their brother Conrad.

Irene married Lionel Woodhouse, who worked for the Ceylon Civil Service. He collected butterflies and gave his collection to the crown. He wrote a comprehensive book on all the butterflies in Sri Lanka. They lived in Sri Lanka whilst Lionel was working and then retired back to live in Sussex.

Evelyn married George Dawson Templer who also worked for the Ceylon Civil Service. They are written up elsewhere on this website.

An account by Dora Montefiore nee Fuller of her and Florence’s early life in “

Childhood

I was born on December 20th, 1851, the eighth child and the fifth daughter of Francis and Mary Ann Fuller, of Kenley Manor, Surrey. Five other children were born after me, and we all grew up to manhood and womanhood in the way the large families of those days seemed to grow up in huge rambling houses, containing nurseries, schoolrooms, servants’ quarters, and three or four spare rooms—all of the house, from garret to cellar being kept in perfect order by a large and efficient staff of servants and under-servants. Of course, during my unconscious nursery and schoolroom days I knew nothing of the domestic machinery which kept this sort of patriarchal home going, but I have since often heard my mother tell of how she was taking her elder daughters out into society while she still had a nursery full of little ones; and I can still remember as a nursery child my mother’s visits at regular and stated hours to the nursery, when she sat on a low chair by the fire and breast-fed the latest baby, while we little ones pressed round her, showing our toys and picture books, with subconscious longings for the touch of her beautiful soft hand on hair or shoulder. The Victorian mothers, it seems to me (in spite of the fact that the lives of their children were mainly passed in the nursery and in the daily care of nurse and under-nurse), took their maternal duties very seriously, for on these occasions of nursery visits our health was enquired into, special orders about feeding and clothing were given, and Nannie reported anything about her charges that required immediate attention. I can see my old Nannie now, of whom I was very fond, sitting by the hour in the same low chair by the fire in which my mother sat when she visited our nursery, and quilling up endless yards of valenciennes lace, interspersed with little white satin bows for the lace caps always worn by Victorian babies; or preparing the tiny filmy shirts and soft warm flannels which were to cover baby’s struggling limbs after the bath which the under-nurse was preparing, and which we elder children loved so to watch. There was a ritual, a seriousness about all the processes connected with Victorian baby-cult, which it appears to me has gone the way of large families, large houses, and large staffs of servants. We have had to simplify life, and baby goes without a lace cap, which is all the better for it, and is shortcoated at the end of weeks instead of at the end of months, which doubtless is all the better for the growth of its lower limbs. But there was a feeling of nest-like warmth about the Victorian nursery, and about the fostering care of the dignified “old nurse,” who took over the charge of each new baby, without ever letting the ex-baby toddler feel that its wee nose was out of joint; and who, even when we were one after the other promoted from nursery to schoolroom, kept a motherly eye on our health, was ready to receive confidences and to give advice, and was always the kindly and sympathetic recipient of the stories of our schoolroom pranks and punishments. Our under-nurses were often Swiss girls, who taught us to speak French and German; and though perhaps from what I now know, their accents were not as pure in either language as they might have been, still I know no better way to délier la langue of young children so as to make foreign languages come more easily in school days, than to let them pick up unconsciously at a very early age the rudiments of one or other languages, in the same way as they pick up the rudiments of their own language.

Every evening we were dressed to go down to the drawing-room for the children’s hour, from six to seven, when my dear father had returned home, and we small people were made joyful by his sunny smile and the way in which he entered into our fun and games and devised glorious surprises for us. On Sundays only we were admitted to dessert, and we sat ready dressed round the nursery, waiting impatiently for the upstairs nursery bell to ring, which was the summons for Nannie in her black silk dress to bring us down. We were supposed to enter the dining room in an orderly little file, but, at the last moment, as the door was opened, our progress generally ended in a rush and a whoop as we hunted for father, who had perhaps hidden behind the curtains, or under the table, or had devised some new and (in our judgment) some exquisite way of cutting up and serving oranges, either as lobsters or as little baskets of fruit with handles—the latter arrangement being our great joy. Then Nannie was given by my father her glass of port wine. We children each had our little glass of sweet Cape wine, in which to drink the health of absent friends, and then we settled down to the wholehearted enjoyment of children (whose nursery fare was of the simplest) of preserved ginger, almonds and raisins, and damson cheese. I can remember no severer punishment in my childhood than being sent to bed instead of going down to the drawing-room at six o’clock for the children’s hour; and when I was the luckless culprit who had to undergo this punishment, I can recall now the shame I felt as I hid my head, sobbing under the bedclothes, and thought of the pain I was causing my dear father, when he would miss me, either from the drawing-room in winter, or the garden in summer, and would learn on enquiry that his little dark-haired girl had been naughty. I was the only brown-haired child in a family of thirteen very fair children, and when visitors were staying in the house, I can still remember the shrinking with which I used almost to expect the remark: “This is not one of yours, Mrs. Fuller?” or, “Is this a little friend or cousin staying with them?” as we filed into the drawing-room. I seemed to think there was a sort of malicious brand on me, marking me out as different, and less well-favoured than the others; and when I was old enough to read the story of “The Ugly Duckling,” I knew exactly what its feelings were, poor dear, and felt oddly and tenderly drawn towards it. Added to this, the fact that two boys came before me in the family made me something of a tomboy and excited the scorn of my four elder sisters, who were grown, or growing up, young ladies, enjoying delightful singing and piano lessons, while I was climbing trees and tearing my frocks. Of these four elder sisters, the eldest married quite young (my youngest sister being then an infant in arms), the second and much beloved one was an invalid (arthritis) from the age of fourteen, and died when twenty-seven. The third became a Sister at Wantage, and the fourth did not marry. A brother was the eldest of the family. He went out to Australia and married there, so that to us younger ones he was little more than a name. Of the two brothers just older than myself, one went into the Indian Civil Service, and the other into the Navy. Two sisters followed me in the family list, then two brothers, and finally one more sister. Of all these brothers and sisters, only one younger sister now remains, while the graves of the others lie scattered in many lands.

Unlike the impressions of most Victorian children, I seem to remember that Sundays, though they had their drawbacks, were one of the happiest days in the week, because of the pure pagan joy of a walk home from old Coulsdon church with my father, who was such a delightful companion in fields and woods, knowing, as he did, the song or cry of every bird and small animal, having always something interesting to tell us about the growing crops, the naughty poppies among the corn, whose flowers we thought brave and brilliant, but which we were told were a sign of bad farming; the fluttering larks, whose outpourings in the clear summer blue we had just been listening to with rapture, and who, as father pointed out to us, never came to earth near their nests, but some distance away, so as not to reveal the secret hiding place of the warm eggs or of the unfledged young ones. Our home was at Kenley Manor House, which looked out over Kenley Common, only divided from it by a ha-ha sunk fence. Our drive to church was over this common, and I can recall now the pleasant soft feeling of driving over the turf; but the moment of leaving church, when father said at the churchyard gate, where the carriage was waiting: “Well, who’s for a walk home?” was, I know for me, the happy moment of the whole day. Eager little hands were thrust into his, and eager little voices cried, “Me, me.” A choice of two or three candidates was made, the rest being packed into the carriage with my mother and the governess, and our rejoicing little band disappeared into a copse, which led down a straggling field into a cornfield, then through other fields and gates on to a corner of Kenley Common, where, O joy! were the kennels of the Surrey foxhounds, of which my father was the master, and Sam Hills was the huntsman. Of course, we all turned in to see the hounds have their dinner of horseflesh and meal, which was poured out into long troughs; but no hound ventured to leave the wooden platforms on which they lay, hungry and expectant, their beautiful eyes watching the movements of the “whips,” and their sleek ears listening for the call of their own names. Victor, Rodney, Spanker, would answer to their names and come down to feed; while on the side of the ladies, Heartsease, Violet, Daphne, would, to the delight of us children, fall to at the ladies’ trough and soon prove that their appetites were as keen as those of their mates. If Breakspear or Charity tried to slip in before their names were called, a flick of the snaky whipthong sent them yelping back to their bench, and they probably had to wait for their call till the troughs were getting low; but we children could not be lured away from the fascinating sight till every hound was fed, and we had had special interviews with two or three favourites. Then there was generally a caged badger or a tame fox cub to be inspected, after which the walk home over the rest of the common was completed, followed by a scamper upstairs to the nursery early dinner, for which on these occasions we were often, late; but we never thought of feeling hungry, we were too interested and excited, and had so much to tell the others, who had been cut off from our delights. On a frosty winter’s day father would remark as we rushed into the hall and made for the fire: “What about some cherry brandy?” Then home-made cherry brandy would be produced, and we youngsters allowed a cherry each before we were shooed upstairs to our early dinner.

Another picture which comes before me is that of the haymaking parties to which cousins and neighbours came. The party would be fixed for the day on which the hay in one of the larger fields was to be carried, and after romps and games and making nests in the hay, syllabub, made from an old recipe of my grandmother’s, was handed round. This syllabub had to be made at the moment that the cows were milked, because after white wine, strawberries, sugar and spice had been put into exquisite china bowls, the warm milk of a cow was milked into this decoction. I cannot remember that we children and our small friends appreciated this syllabub very much, but no doubt it made its appeal to the grown-ups, as I always remember, even when I had reached the schoolroom age, it being made and handed round in bowls of which I loved the feel, because the china was so delicate. After syllabub came tea in the field, followed by riding on the piled-up hay carts as they swung through the gates and up to the great stack in the stack-yard. Kenley Manor had a home farm, which was managed by the bailiff; and another of my great joys as a child was going round the farm and stables with my father on a Saturday afternoon, or summer evening, listening to his chats with bailiff, head groom or head gardener, for he was country born and bred, and not only loved, but understood and reverenced the varying and intimate expressions of country life. In the gardens and hothouses, with their grapes, peaches and melons, I learnt much valuable garden lore, for my father kept abreast with what was latest in garden culture, and made frequent visits with his friend, Mr. Robinson, the editor of The Garden, to the public gardens and parks of Paris, where the latest phases of nineteenth century gardening were to be studied. As regards the feeding of plants, I always remember his telling a guest who was struck with the size and lusciousness of some Black Hambro grapes in one of the hothouses, that a calf which had died on the farm had been buried at the root of that particular vine; and I have often watched when a child, the liquid manure being applied to the strawberry plants at the moment the fruit was forming, so as to give strength to the plant at that critical moment. Among our friends our strawberries were renowned, and we children always rejoiced that our holidays began about June 18th (the school terms were at that time four instead of three, as now), because strawberries were ripe at the time when school broke up for summer holidays.

My elder sisters rode to hounds constantly with my father. We younger ones had our ponies, and sometimes as a special treat rode before breakfast with my father, who taught us with an old steady white pony called Snowball, both to ride and drive, being specially particular about our understanding harnessing and unharnessing when driving, and the tightening of girths before mounting to ride; for he explained that accidents often happened because of ignorance on these points. He also kept a strict watch on our hands when riding or driving, to ensure our always feeling sensitively the pony’s mouth, and never committing the sin of jerking at the bit. His own hunters and roadsters were to him intimate friends; and he had mounted as an inkstand the hoof of a favourite mare, aged twenty-seven years, which he used constantly to drive in a light gig down to Brighton before the days of railways—returning the next day. He was, even at the age of eighty, a wonderful shot, but he never cared for driven game. His enjoyment consisted in walking over the stubble fields or turnips with a friend or two, equally keen at birds, and watching the dogs working. He would eat with relish for his lunch a turnip pulled up from the field and scraped with his knife; and I can remember his telling of how in his youth the tenant farmers used to put up in their turnip fields for the instruction of passers-by “Take one, and a’ done; take two, and I’ll take you.”

My father read prayers in the dining-room every morning, and in the drawing-room at night; all the children from nursery and schoolroom attending in the morning, with a row of servants near the door. When I look back at those happy sheltered days of what I suppose was a more or less typical Victorian home life, I note the vast difference that separates the psychology of parents, children and the domestic staff from that of the twentieth century. The same old nurse took charge of one baby after another, as about every two years a small son or daughter put in an appearance. The same governess fairly young when she took over the education of my elder brothers and sisters, was d’un age mur when it came to my turn to begin schoolroom lessons; but even when past teaching young and troublesome youngsters, whose eyes were always wandering towards the garden, and whose thoughts were thirsting for a jump across the ha-ha and a ramble round the common, or a climb into one of the old oak trees that flanked the lawn—she remained a pensioned family friend, always ready to take us children to the seaside in summer if my mother was otherwise engaged; or even to stay as a “parlour boarder” with two of my elder sisters at a French school in Paris, so that she might accompany them to the Embassy Church on Sundays and read English literature to them as a steadying counterblast to French ways and French accomplishments. My father’s love of English literature was very great, though nowadays his tastes would no doubt be thought narrow and old-fashioned. It was he who first pointed out to me (then a child of ten) the inherent beauties of simplicity and of classical purity in Gray’s “Elegy in a Country Churchyard,” and induced me to learn it by heart, telling me I should never understand all its English soul and essence, till I had memorised it. He always maintained that Shakespeare had something to say on every subject, no matter how modern it might be; and when discussions arose on questions of the day he would interject, taking down his Concordance: “Let’s see what old Shakespeare has to say about it.” He generally found something near the mark, and this hunting up of quotations gave me at least a fair working knowledge of the plays and sonnets of Shakespeare, so that I was able when twelve years old to make my own birthday book of Shakespearian quotations, in days before printed birthday books were the fashion. I have the old book still, written in my schoolgirl handwriting. The quotation I chose for my father was, “The elements so mixed in him that nature might stand up and say to all the world, this was a man”; and for my mother, “Many days shall see her, and yet no day without a deed to crown it.”

Early Impressions

As the trailing clouds of childhood’s fantasy rolled slowly away, I became conscious, not only of myself and of my immediate nest-like surroundings, but of the dim reverberations of outside events which came throbbing into our sheltered home. We were standing, a little clutch of girls and boys round the piano on which my mother was playing the accompaniment of a song:“Oh! it’s a nice little island,

Nice little, tight little island;

Devil or Don, let him come on,

But he shan’t get a bit of our island.”

I enjoyed shouting with the others the doggerel lines; but afterwards, with childish intellectual curiosity, I began to wonder what it was all about. “Devil” was in ordinary social intercourse a word we were not allowed to use (though my brothers in their holidays flung it around in the schoolroom when our governess was not there), so I pondered long on the problem as to who this particular “Devil” could be, who along with “Don” appeared to threaten our island and, incidentally, our home and myself. So at last I took my difficulties to my father and learnt that we had just beaten Russia in a war, and that was what the song was about. “But do devils and Dons live in Russia?” I queried; and my father, instead of giving a direct answer, fetched a map of Europe and pointed out to me the Crimea, where the fighting had been, showed me what a long way it was to send from England, by sea to the Crimea, the men, provisions, guns and ammunition, and told me something of the sufferings through the long winter of our troops and of the French, who were our friends and allies. “But didn’t the devils and Dons suffer also?” I cried, with tears in my eyes, for I hated cold. And then without waiting for an answer: “But why did the Russians want to come to England when they had all that big country to live in?” To this last question I never received a satisfactory answer, and I still fear that the writer of “The Tight Little Island,” which it was such good fun to sing, was exploiting the facile patriotism of children and of uninstructed folk. There were other chanties that also made an impression on my youthful emotions, as my mother played the accompaniments and led the singing. “There is a happy land, far, far away” sounded comforting and reassuring for the future, especially after the under-nurses’ threats of Hell, and the rumblings on the subject in church; but when “There is a fountain filled with blood” was sung, I saw the brimming fountains in Trafalgar Square slopping over with red gore, and in an ecstasy of self-imposed horror, I closed my eyes and put my fingers in my ears, and when asked what was the matter, refused obstinately to reply.

Another imperious impression from the outside world comes to me when I remember being taken in hushed horror into my mother’s room to see my father in bed with his head swathed in white bandages. It had been explained to me that he had been on the trial run of a very big ship called “The Great Eastern,”—which was built to carry the cable across the Atlantic, in order to connect England and America by telegraphic communications. My father’s life-long friend, Scott Russell, had planned and laid down the lines of the great ship, and he had invited my father, among others, for the trial trip. The two friends were pacing the deck, when one of the boilers exploded, and a falling piece of hot iron cut through my father’s top hat and caused a scalp wound. Some members of the crew were, I believe, killed, and it was explained to me that it was only father’s hard top hat that saved his life. He looked so different from my handsome, fresh-coloured father-friend as he lay bandaged in a darkened room, that I wanted to run away and cry; but his eyes smiled, and he beckoned to me that I was to scramble on to the bed and kiss him, so I was partly comforted before nurse led me away.

My father was by profession a land surveyor and estate agent; and he surveyed and valued the land for all the early railways. Purley Station was our nearest connection on the London and Brighton Line and my father wanted that company, of which he was for many years the surveyor, to make a branch line from Purley up the valley to Caterham, pointing out that London’s southern suburbs must develop in that direction and that land values would improve enormously if such a branch line were carried out. He was unsuccessful in persuading the Company and decided to make a line (a single one) himself, and at his own expense. Later on, when my father’s prophecy was fulfilled and Caterham Valley became a favourite railway suburb, the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway bought the line of him, and made it a double one. As he was born and had been brought up at Coulsdon Court, near the head of the valley, he had ridden and hunted every inch of land in the district, and knew every fence and bridle path of the countryside; I have heard from many of his contemporaries what an extraordinary gift he had of valuing standing crops with lands and buildings, and he foresaw accurately future values after railways had opened up a new district. All these matters I used to hear discussed from time to time when in the drawing-room; and sometimes one or other of us youngsters would be allowed to drive down with the groom to meet my father at Kenley Station on this branch line, when father would take the reins and drive home, and I perched up beside him would keep up a running fire of shy questions about all the things that had puzzled me during the daytime, and the matters I had heard talked about in the drawing-room the night before; for the charm to me of my father’s answers was that he never laughed at me or gave me puzzling answers as some people used to do, but spoke to me, I felt, out of the fullness of his own knowledge and with a real desire to help my ignorance and stimulate my opening intelligence.

He used to tell me that the branch of the Fuller family we belonged to, was that of the Fullers of Rose Hill; not direct descendants of the old Fuller, M.P., whose bust (placed there by local admirers) is in Brightling Church, Sussex—for he never married; but collateral descendants. That old eighteenth-century character lies buried in Brightling churchyard under a most massive and ungainly brick pyramid. A delightful parliamentary story is told about him, which I have often enjoyed thinking about during my Woman Suffrage work, and in later years when asked to contest a parliamentary seat. The old gentleman appears to have been irascible, and his language was not always kept within parliamentary bounds. On one occasion when he had transgressed, the Speaker demanded an apology to the House, and as at that period the apology had to be made by the contumacious member on his knees, Mr. Fuller went through the whole prescribed performance, but, as he rose, he dusted his knees with his handkerchief and remarked: “And a damned dirty House, too.” It has occurred to me sometimes in later life, when I listened to lifeless and insincere debates at Westminster, or interviewed Members of Parliament, whom I found too often ignorant and prejudiced about the subjects on which many of us women had thought deeply, that I had inherited some of the parliamentary disillusionment which was evidently part of the make-up of old Mr. Fuller of Rosehill; and when I read William Morris’ strictures on Parliament, I realised that, though it was none the less necessary for us women to insist on obtaining political citizenship, it would really go a very little way towards our economic and social emancipation. That would be another story.

As my father had been in reality the initiator of the first Great Exhibition in 1851, he naturally had constantly around him the men of thought and action of that early Victorian period. My father being a member of the Society of Arts, of which the Prince Consort was the President, he at a meeting of the Society on 30th June, 1849, was introduced by Mr. Thomas Cubitt to His Royal Highness in order that the Prince might afford him an opportunity of stating his opinion as to the desirability of founding in London an exhibition of the industry of all nations, which project my father had fully explained to Mr. Cubitt on June 12th, (page 224 of the minutes of the meetings of the promoters of the Great Exhibition, 1851). As the result of this and further interviews the task of making enquiries of the manufacturers throughout the Kingdom as to the advisability of holding such an Exhibition was entrusted to Mr. Scott Russell, my father (Mr. Francis Fuller) and Mr. Henry Cole.

As the result of this official enquiry among manufacturers throughout the United Kingdom, the scheme for launching the Great Exhibition in 1851 was continued under the presidency of the late. Prince Consort, who worked personally and assiduously to make the Exhibition the real success that it later on became. The guaranteed fund on which the Bank of England advanced money was organised, and in view of the Wembley Exhibition which has lately taken place, and which financially has not been the entire success that was expected, it may be of interest to give here the names of the subscribers to the guaranteed fund of the 1851 Exhibition.

| Albert Buccleuch Overstone Ellesmere Stanley Ross Granville Lord John Russell Sir Robert Peel Sir A. Gallaway Sir C. Lyell Sir R. Westmacot Rt. Hon. T. Baring Mr. Labouchere T.M. Gibson W.E. Gladstone S.M. Peto William Cubitt Robert Stephenson Richard Cobden Thomas Beezley Charles Barron C.W. Eastlake P. Pusey W. Thompson C. W. Dilke Henry Cole Francis Fuller | 10,000 10,000 10,000 10,000 5,000 5,000 5,000 10,000 5,000 1,000 1,000 10,000 5,000 5,000 5,000 50,000 5,000 10,000 1,000 1,000 5,000 1,000 1,000 5,000 1,000 500 20,000 |

Among other items of interest may be noted that the privilege to sell refreshments under the rules and regulations published by the Executive Committee was granted to Messrs. Schweppes for the sum of £5,500. The privilege of selling the catalogue was granted to Messrs. Spicer & Son for the sum of £3,200, and an additional 2d. per catalogue for all sold over and above 500,000 of the small edition and 5,000 of the large. Mr. Bennett (later Sir John Bennett), watchmaker in the City, gave £750 for the right to advertise on the last page. My father was one of the early Commissioners entrusted with the carrying out of the scheme in all its details, and the profits of the undertaking when the exhibition was closed and accounts were made up, amounted to the sum of £200,000, which sum was part of the endowments used to build and equip the South Kensington Museum. As is well known, the Crystal Palace at Sydenham is, with certain additions, the structure of the Hyde Park Exhibition of 1851. My father surveyed and bought for the Crystal Palace Company a beautiful site at Sydenham where the Crystal Palace stands. The Hyde Park Exhibition closed on the 15th October, 1851. A first column of the Crystal Palace was raised into its place on the 5th August, 1852. In an article in the morning Advertiser of the 27th May, 1876, it is stated that “During this brief interval, the ideas to which the new building was to be dedicated were completely matured, a whole scheme was perfected, a company formed with a body of able and practical gentlemen as its directors, a charge of incorporation obtained and the services of numerous eminent men belonging to various professions, or whose names have been long identified with various branches of art and science, were engaged to superintend the several departments and the numerous works and ornaments, which, in the aggregate, were to form the Crystal Palace, with its vast appliances for instruction and its unequalled appenage of sylvan beauty.’” Such was the inspiration of those who founded the Crystal Palace and filled it with courts and treasures of educational and aesthetic value; and from among these founders and workers a group of artists, musicians and literary men surrounded my father, who was the first Director of the enterprise, and who at the end of the period of directorship was able to show a successful balance sheet as the result of the labours of himself and others. For his work and generous devotion in initiating and helping to carry to a successful issue the first Great International Exhibition, my father was offered, but declined, knighthood—and knighthoods were not thrown about in those days as they are now.

As I grew up I remember intimates of my parents’ home circle, such as Arthur Sullivan, Carter Hall, George Cruikshank, George Grove, Labouchere, Scott Russell and many others of that period; and I as a schoolgirl loved to listen to the really good talks on every subject of interest of the day which I heard in my home surroundings. Later on, when I was sent to Miss Cresswell’s school in Sussex Square, Brighton, I naturally knew less of what was going on at home, but I was always able to keep up in thought with my father’s work and activities, for in the holiday time I had the privilege of being his reader; and every subject, either in the newspapers or magazines of the day, or in any book of the moment which I read aloud to him, we discussed fully, and he was able to throw for me much light on the various questions of politics, art or literature. Still later on when I had left school and his health was not so good, I became his amanuensis, for he was then writing much on social questions and preparing papers to be read at the British Association or at Social Science Congresses. “Waste Labour to Waste Land” was one of the subjects in which he was deeply interested, for he already foresaw the difficulties under which agriculture was later on to suffer, and was also already alarmed at the then very moderate figures of unemployment. He realised also that Great Britain could, and should be, self-supporting where wheat, and to a great extent meat, are concerned. His great pleasure in the summer holidays was to go abroad with some of us young ones to collect information about scientific farming, afforestation and intensive culture of fruit and vegetables on the Continent. Languages coming easily to me as I, thanks to his care, had been thoroughly well taught both French and German, he used me as his interpreter, and many were my difficulties in these languages when it came to asking technical questions and receiving highly technical replies. But the pleasure to me of these Continental trips was so great and the benefit to me in these technical encounters was so extreme as regards general knowledge, that I look back to these days of travel with my father as some of the happiest and most valuable in my life.

About my school at Brighton I must confess that though it was in some respects strict and later Victorian, the education was extraordinarily good. Besides a large and efficient staff of teachers, including a French and German governess always in residence, we had professors for many subjects, such as mathematics, science, French literature and a very excellent teacher of pianoforte in Mr. Goss. We spoke German all the morning and French all the afternoon, but were allowed when out for our walks to talk English with one another. We had to attend numbers of missionary meetings, which I loathed, and besides two church services on Sunday had endless religious exercises such as repeating of catechisms and collects between the hours of services. This overdoing of doctrinal teaching alienated, I am convinced, many of the pupils from church going, and made prigs and hypocrites of others; but once Sunday was over the school curriculum with its regular duties and studies appealed to me vastly. Great pains were taken with our reading aloud, with pronunciation and with what the French call diction; and I have often in later life felt grateful that this was the case.

At eighteen I left school and at the same time ceased to be a schoolroom young person; that is, I was admitted to late dinner, had a coming-out party, and attended with one or other of my sisters any dances, balls or entertainments that were the order of the day. But I went on with some of my studies, especially drawing and painting, and continued to write for my father and help him in his work, accompanying him in the summer to Archaeological, Social Science, British Association, and other meetings, and visiting with .him the old friends and fellow-workers of the strenuous ’fifties and ’sixties. I have mentioned George Cruikshank as being a frequent visitor to our home, and I can still remember the mischievous delight with which we young ones in the safe seclusion of the schoolroom discussed his eccentricities both of beliefs and personality. As is well known, he was a rabid teetotaller, and I can remember him taking us children into the hot-houses where the grapes were hanging in rich and ripe bunches, and pointing out to us that nature had provided for each grape an exquisite skin which protected the luscious juice inside from fermentation. This scheme of nature, he averred, was planned with the intention of mankind eating the grape in its unfermented state, but man, with his evil cleverness, had learnt to break and crush that exquisite skin so that the juice of the grape might ferment and turn to alcohol, which was drunk in the form of wine. I suppose that as he observed all of us young people coming to dessert and drinking our glass of sweet wine, he thought it his duty to inculcate this special lesson, but I fear we only did as my father did, smiled indulgently, for though father appreciated George Cruikshank as a man and as an artist, he did not admire his philosophy as expressed in the “Triumph of Bacchus,” that extraordinary picture in the South Kensington Museum. Old George Cruikshank was practically bald, but he had a long mesh of iron grey hair which he trained across the top of his head and kept in its place with a piece of elastic, which arrangement was the delight of us young ones, as it was the only coiffure of that sort we had ever seen. My elder sisters had good and carefully-trained voices and sang delightfully both part songs and solos, so we had constant musical evenings in our home, and my father loved to fill the house with musicians at weekends. He bought largely and with good discrimination at the various art exhibitions and possessed at one time one of the best water-colour collections of the day. The house was full of Landseers, Sants, Prouts, Coilingwood-Smiths, Birkett-Fosters and Tidyes pictures, and I remember that from a small child one or two of the pictures in his collection held a special fascination for me. One was an exquisite study by Sant of “Motherhood,” and the other a picture of the French Revolution by an artist whose name I do not remember. The incident was that of Mlle. de Sombreuil drinking a glass of blood handed to her by one of the revolutionaries on the understanding that if she swallowed it her father’s life would be spared. The face of the old father aristocrat, the faces of the crowd, and the agony of the girl torn between her love for her father and her shrinking from the revolting ordeal, used to haunt my imagination for nights and days, and I have often wondered since I grew up and left home, who had become the possessor of that picture when my father’s collection was dispersed. I think if I had owned it I would have had it destroyed, but perhaps that thought is the remains of childish impressionability.

My eldest brother was married and living in Australia. His wife was delicate, and he wrote to ask that one of his sisters should come out on a visit and help her with the children and the housekeeping. It was decided that I should be the one to undertake this duty, and I went out under the charge of a cousin to stay in my brother’s house. This was how I first came to know Australia and Sydney. Sir Hercules Robinson was at that time Governor of New South Wales, and I had introductions to Lady Robinson and other friends out there. It was there I met my future husband, Mr. George Barrow Montefiore, but I returned home before marrying him, was introduced to his family and spent some months among my own people. Then in 1879 I went out again, was married, and we lived in Sydney, where my two children were born. In 1889 my husband died and I was left with a daughter of five and a son two years old.

It was after the death of my husband, when I had to go into business matters with trustees and lawyers that I had my initiation into what the real social position of a widow meant to a nineteenth-century woman. One lawyer remarked to me, when explaining the terms of the will: “As your late husband says nothing about the guardianship of the children, they will remain under your care.” I restrained my anger at what appeared to me to be an officious and unnecessary remark and replied, “Naturally, my husband would never have thought of leaving anyone else as their guardian.” “As there is a difference in your religions,” he continued grimly, “he might very well have left someone of his own religion as their guardian.” “What! my children, the children I bore, left to the guardianship of someone else! The idea would never have entered his mind, and what’s more, I don’t believe he could have done it, for children belong even more to a mother than to a father!” “Not in law,” the men round the table interjected; while the lawyer who had first undertaken my enlightenment added dryly: “In law, the child of the married woman has only one parent, and that is the father.” I suppose he saw symptoms of my rising anger, for he appeared to enjoy putting what he thought was a final extinguisher on my independence of thought; but I could hardly believe my ears, when this infamous statement of fact was made, and blazing with anger, I replied: “If that is the state of the law, a woman is much better off as a man’s mistress than as his wife, as far as her children are concerned.” “Hush,” a more friendly man’s voice near me remarked. “You must not say such things.” “But I must and shall say them,” I retorted. “You don’t know how your horrible law is insulting all motherhood.” And from that moment I was a suffragist (though I did not realise it at the time) and determined to alter the law.

After my father’s death at the age of eighty, my mother lived at St. Aubyns, Hove, where I subsequently returned and lived with or near her for some time. It was during the early years of my widowhood, while still living in Sydney, that I met Sir George Grey, who had come to Sydney from Hobart with his niece, Mrs. George, on the occasion of the federation of the Australian States. Sir George’s work in the colonies of New Zealand, South Australia and South Africa is well known; and as a maker of Constitutions for these new colonies he was consulted as a specialist to advise on the Australian Federal Constitution in the making. I had the privilege of seeing him constantly at this time, and of having most intimate talks with him on his past work, and on his future ideals for the British colonies. He addressed a great meeting at Sydney Town Hall on the question of “One man one vote,” when Mrs. George and I were the only women present, and we sat on the platform and watched the huge enthusiastic and interested crowd of men in the body of the hall. It was almost my first introduction to politics and to public meetings, and I felt that here, indeed, was something worth while in my life which, since the death of my husband and my father, I had looked upon as more or less of a closed chapter, as far as interests outside my borne were concerned. When I spoke to Sir George Grey on this negative aspect of things, which seemed to be shutting me in, and cutting me off from interest in life (for I no longer cared for the balls, picnics and race meetings which had filled to overflowing my short married life), he made it his business to re-kindle my interest in social and political questions, the fire of which my father had originally lighted. He told me that I had so much more general knowledge than had most women of my age, and that I had been so much in contact with masculine minds, that I was able to sift evidence and form my consequent opinions in a way which was different from the processes of thought of most women and that I should try and specialise on political and social questions. He spoke to me of the enfranchisement of women in the colonies, where things moved more rapidly than in the older countries, and said that such legislation would lead the way for similar reforms Great Britain and elsewhere. He added that now that the question of Federated Australia was becoming a fait accompli, each State in the Federation was making its own special laws, and in consequence, the women in each State must agitate and organise for political enfranchisement. “That should be your work,” he said to me more than once, “to help found a Women Suffrage League for New South Wales. It has been done in New Zealand, and must be done in each Australia State. Try and find out which members of Parliament would be favourable to the idea, and get together a group of men and women who will work to forward such legislation, and you will find intense interest in the work while it will help you to plan out a new life, side by side with the duties you have at hand in superintending the education of your children.” I took his advice, and the result was eventually that, having found a response to the enquiries made by a small group of women suffragists in Sydney, we founded in 1891 the “Womanhood Suffrage League of New South Wales,” the first meeting: of which were held in my house in Darlinghurst Road in Sydney. As this was the inception of the public part of my life, I think it will be useful for the purposes of developing the history of one section of the Suffrage Movement, now a national and an international one, to give the exact story as told in the minutes kept by Miss Rose Scott, of the early meetings of the Womanhood Suffrage League of New South Wales. When I was in Sydney recently I used often to go up to Miss Scott’s house in Woolhara to talk over with her our work in the past and to discuss the future of women’s organisations in various parts of the world. In connection with the early days of our work together, we had occasion to look up some of the minutes of our first meetings, and with Miss Rose Scott’s permission, I took copies of the minutes of some of the preliminary meetings. These I will now reproduce in a chapter of their own.

Francis Conrad Fisher

Born: 10 May 1850

Dimbulla, Central Province,

Sri Lanka

Died: 2 April 1901

Kurunegala, North Western Province, Sri Lanka

Francis Conrad Fisher was born in Sri Lanka on Dimbulla Coffee estate in the central part of the Island near Nuwara Eliya.

His father William Fisher was an army captain who was one of the first British to explore the central region of Sri Lanka and identify that it had good potential for plantations. He bought himself out of his army commitments and started a Coffee Plantation which he named Wavendon after his home village in England. Unfortunately many of the coffee plantations failed due to a financial crisis and William sold up and became the head of police. After the family had sold the estate it became the first tea estate in Sri Lanka and still produces tea to this day.

Francis’s mother Sophia Lambe was born in Mayfair, London from a fairly successful family. Her great uncle was a successful engraver Josiah Boydell and had been Lord Mayor of London. She went out to Sri Lanka to help run her brothers home and got married to Francis aged 16.

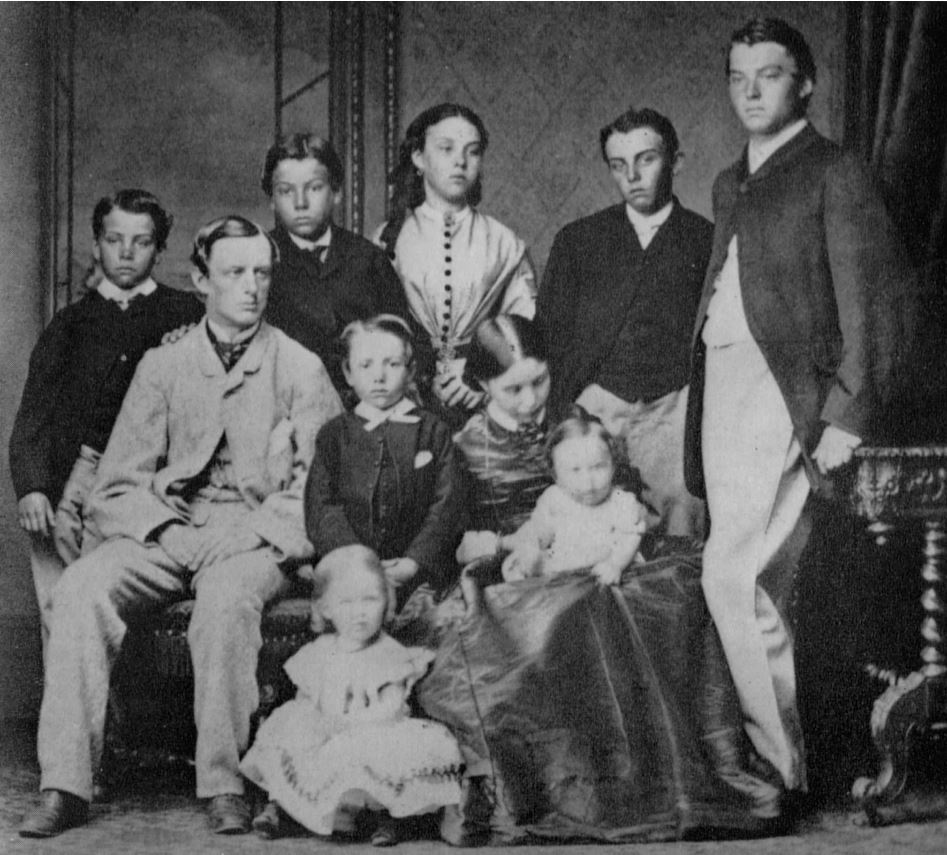

William and Sophia had eleven children. Francis had an elder brother Jack who left Sri Lanka aged 14 but went on to become first Sea Lord of the British Navy. Jack Fisher called Francis Frank.

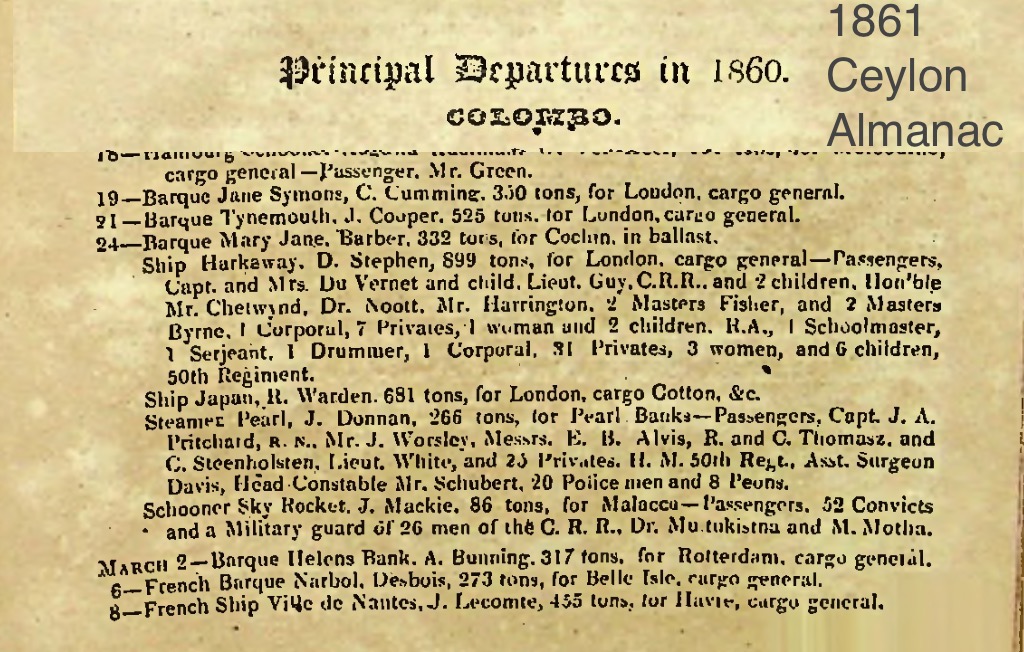

Frank had a fairly free and easy childhood living on the Coffee estates with little studying and lots of hunting. But in 1860 aged 10, Frank and his older brother Arthur (aged 11) travelled on the ship Harkaway to London. They went to Lichfield Grammar school where there sister Lucy Ellen was also studying. His brother Frederick describes that it was a very harsh environment and the boys were regularly beaten.

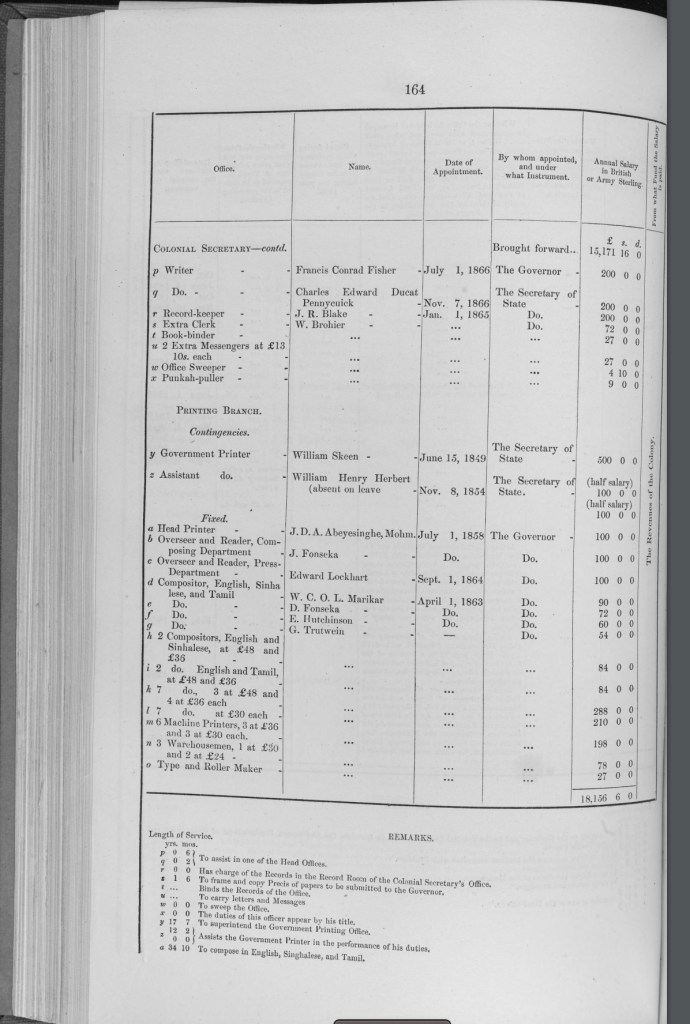

Frank returned to Sri Lanka in 1866. Shortly afterwards his father died from a riding accident. Frank was only 16. Frank joined the Ceylon civil service shortly afterwards. Perhaps he was given the job in order to help the family out .

In 1872 he was visited by his elder brother Jacky (a married man of 31 a that point) who put in at Galle in the ship “Ocean”. It was the first time Jack had met his mother in 26 years so it may have been an emotional visit. Jan Morris’s book about Jacky Fisher has a nice quote about the visit, she says of Jacky Fisher ”On his only return visit to Ceylon, with the frigate “Ocean” in 1872, he was immensely taken with Frank – a perfect specimen of a man, he said, with ” a sort of bold careless proud way about him””.

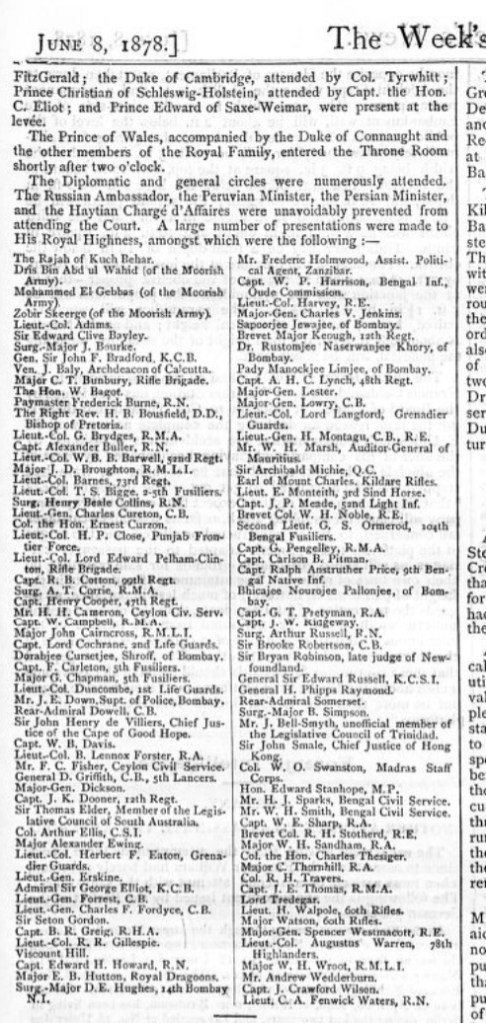

In 1878 he came to England for an audience with the Prince of Wales at a “Levee” this was something of an honour.

In May 1884 he took 3 months sick leave for ill health and came to england. Possibly this is when he met Florence. If so they had a whirlwind romance ! I can imagine that her father although old by this time may well have been interested in his irrigation work which was reported in the paper.

He married Florence in Sussex in September 1884 he had already had several roles in the Ceylon Civil Service. Florence and Francis had three children: Evelyn, Irene and Conrad.

Frank was involved in a number of key projects for the Civil Service. In particular he promoted and then developed an irrigation scheme which meant that part of the population could grow rice. This was a restoration of some ancient irrigation systems. It meant that cheap food and clean water were available and subsequently helped reduce diesease in the area.

He also wrote a key report that criticised a tax on rice and helped repeal some unfortunate and unfair legislation.

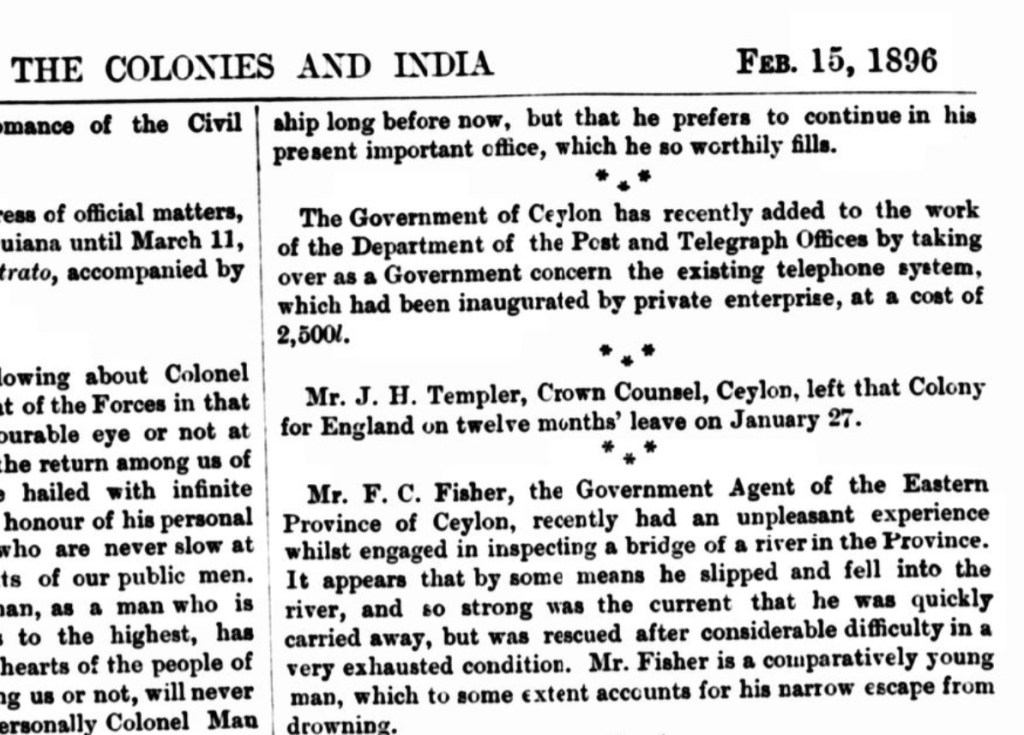

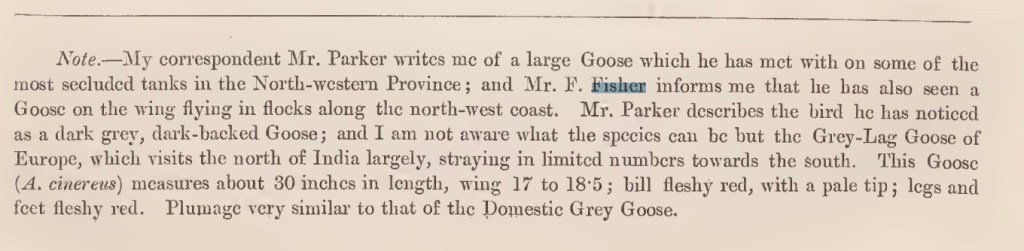

In 1892 Frank took some leave because he was unwell and in 1896 he had a scary incident where he fell into the river and was washed downstream. In 1897 he was again ill and took 3 months off work. However he continued to take an active interest in sport and was President of the Uva Cricket club in 1890.

Francis died as a result of suicide in Sri Lanka aged 50. Looking at his probate records I wonder if he was in financial difficulty. From the newspaper reports it seems that he was a popular man and the fact that he was so unhappy was somewhat unexpected. The last work related report I can find that mentions him was highly critical of his recent report and requested him to restructure his department. I wonder if this had anything to do with his ill health – which is mentioned in the reports of this death.

Frank Honoured in 1878 – Levee with the Prince of Wales

Frank’s work on irrigation

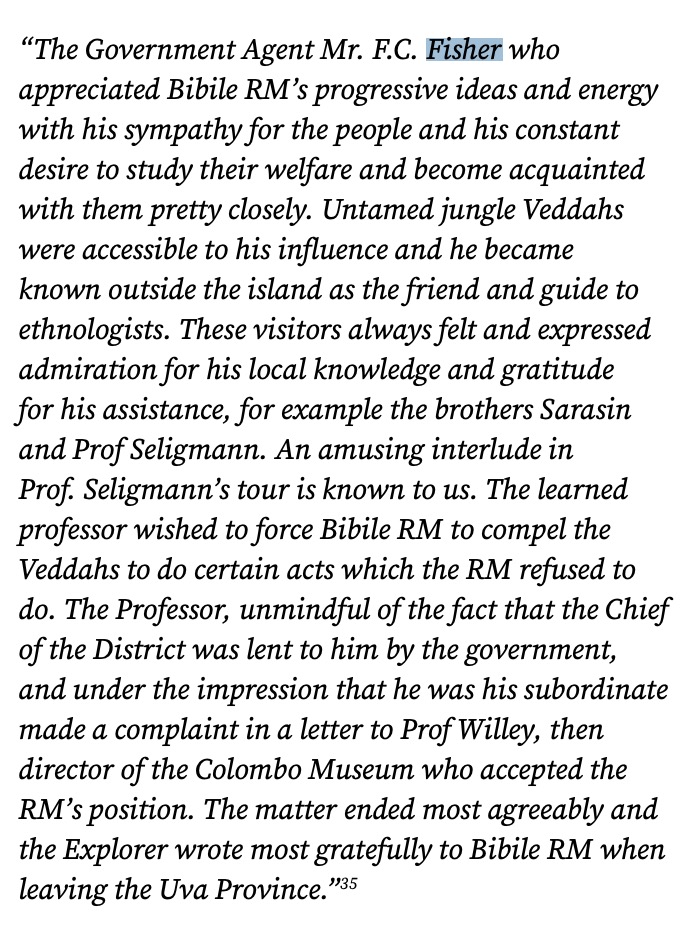

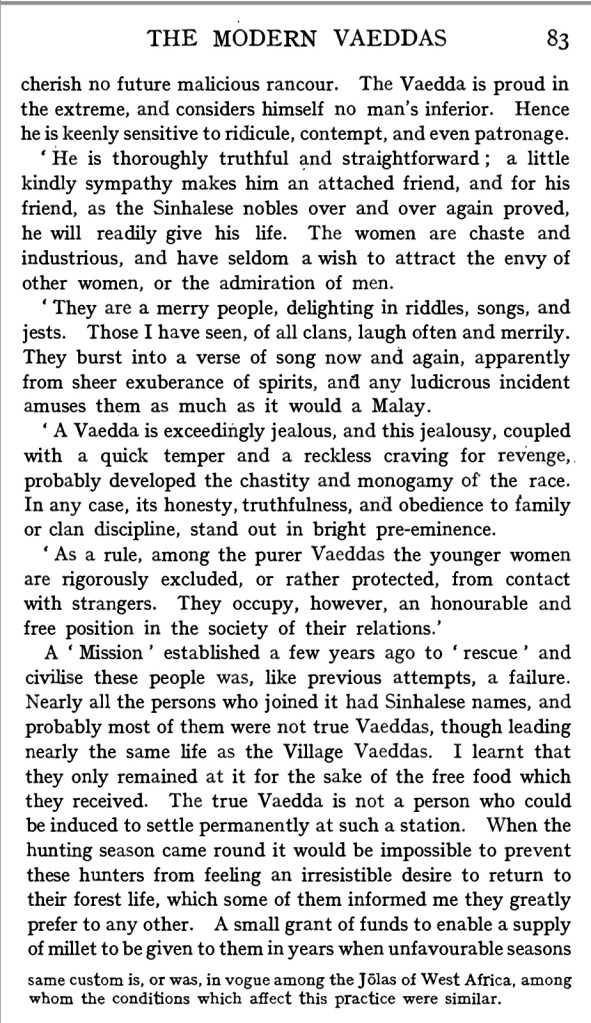

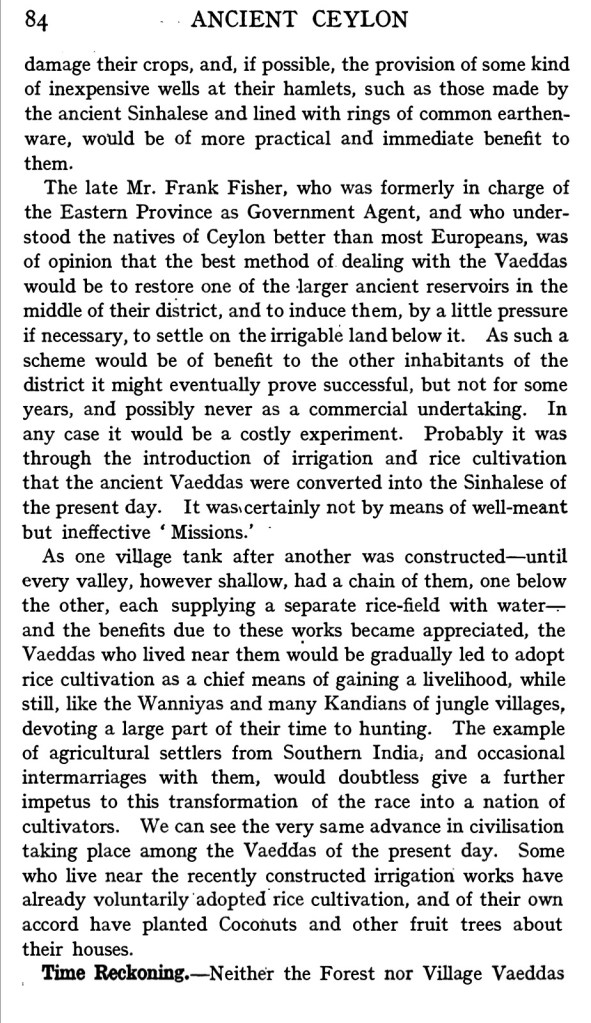

Frank was involved in developing irrigation schemes around Okkampittiya. These were heralded as something of a success. He and Bibile RM one of the leaders of the Veddah population had a mutual respect.

This is a passage enlarged from following document (in case you can’t view it!)

Frank’s work on the rice tax

Frank wrote a key report which lead to the reappeal of an unfair rice tax which was causing considerable deprivation.

Miscellaneous other details about Frank at work and the final review which could perhaps link to his untimely death.

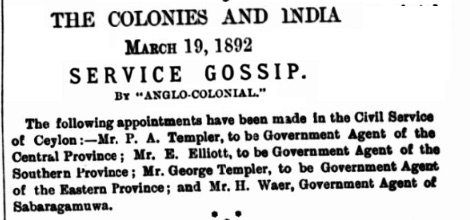

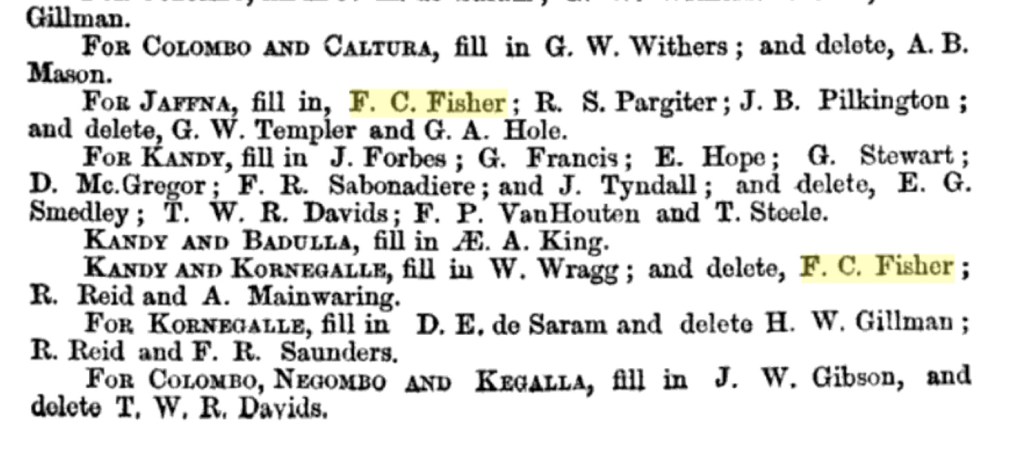

A move from magistrate for Kandy and Kornegalle to Jaffna in 1868. He was 18 at this point. What amuses me is that one of my great great grandfathers is replacing another (G W Templer) as magistrate for Jaffna.

An early report by Fisher in 1870 aged 20 relating to the relations between Planters and the local population which might have lead to the Game Ordinance leglisation below.

I think “peasant orientated” is meant to be a compliment!

Comment on the relative leaniancy of Fisher towards tenants

A very critical account of the work that Fisher had been doing as Acting Conservator where he was asked to reorganise the department in 1899 two years before he died.

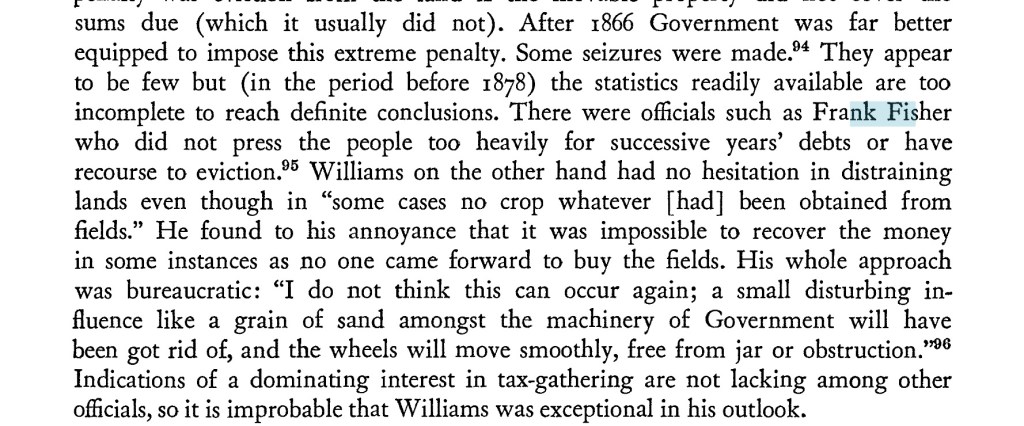

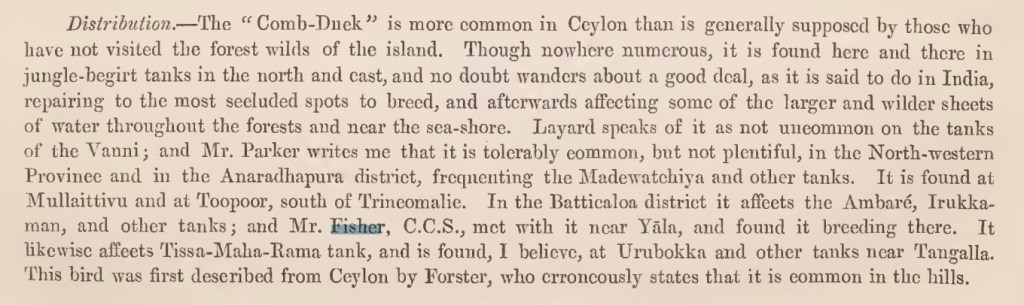

Frank was a keen hunter but also a nature lover

Frank is described as a “true and mighty hunter of big game” in Harry Storey’s “Hunting and Shooting in Ceylon” (1907). But the his underlying love of nature comes out in the quotes I found in “The History of the birds of Ceylon” where he was clearly in dialog with the author Captain W. Vincent Legge (see quotes below)

Frank the sportsman

These are scenes from a famous match against an England team in Nuwara Eliya in 1892. I am pretty sure Frank would have attended this.

Frank’s death in 1901

Francis’s Suicide was somewhat unexpected as these articles testify. I did find that his recent work had been criticised and was under review.

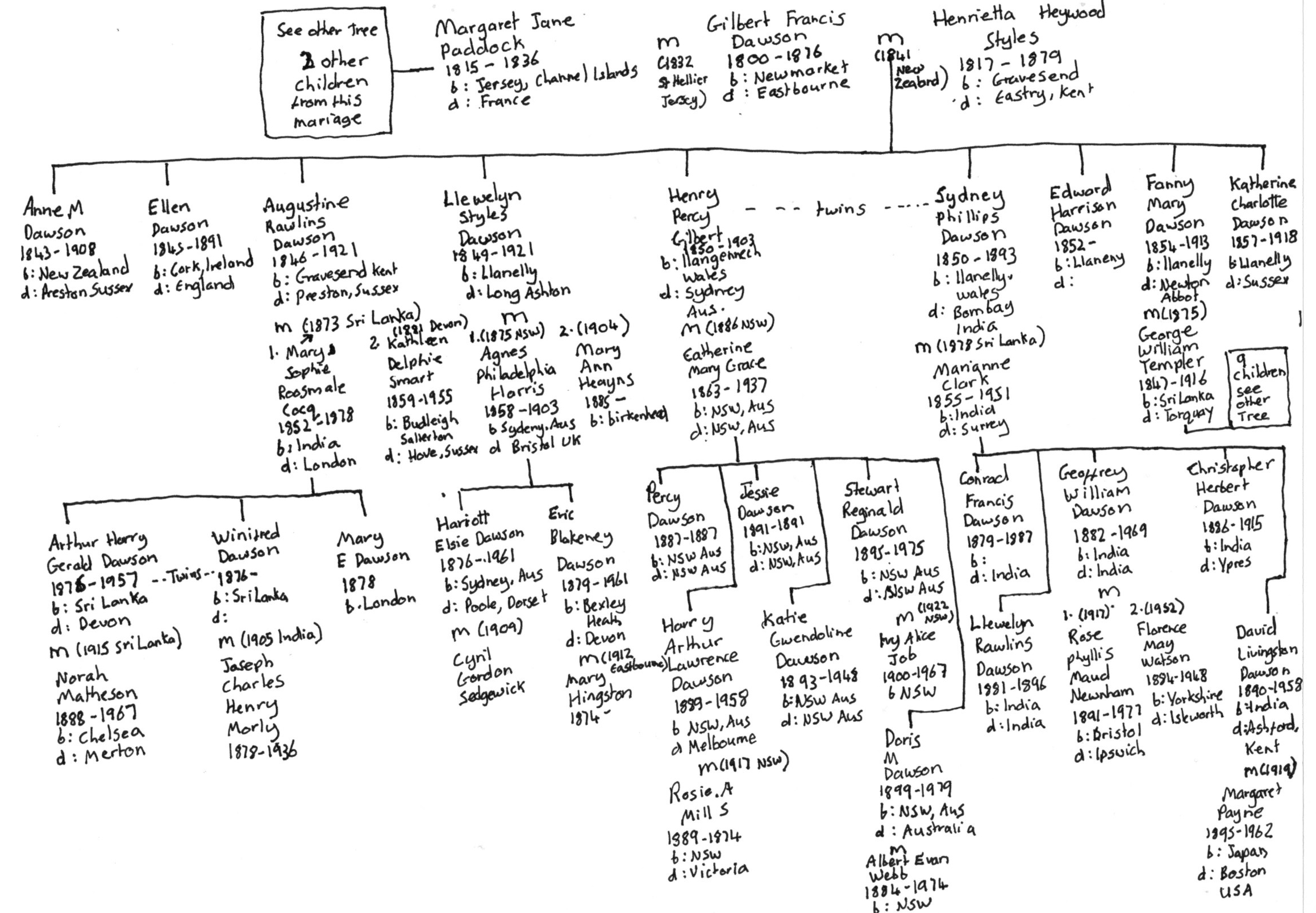

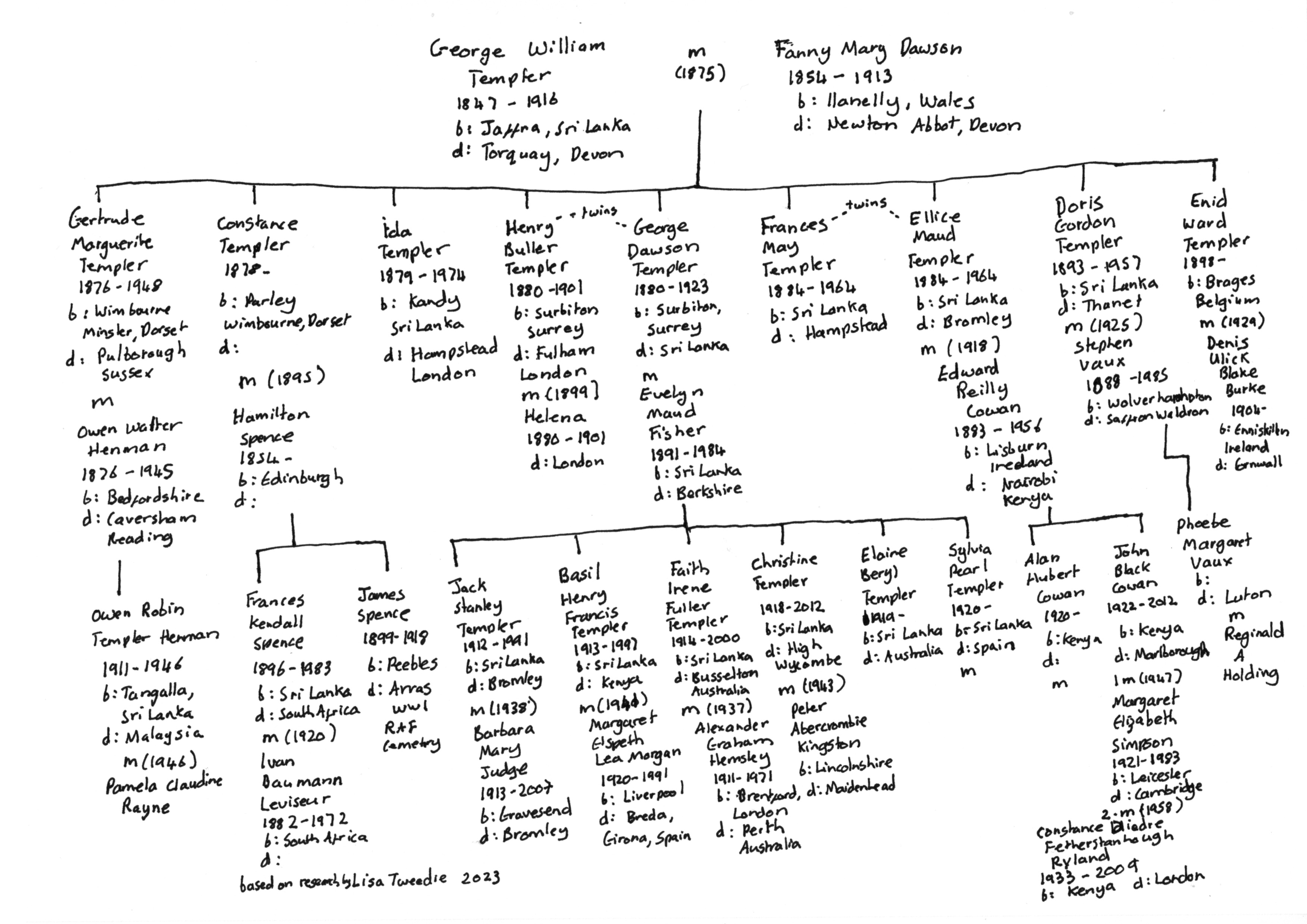

Fanny Mary Dawson

Born: April 1854

Llanelly, Breconshire, Wales

Died: Jan 1913 • Newton Abbot, Devon

Fanny Mary Dawson was born in Llanelly, Breconshire, on the South Coast of Wales.

Her father Gilbert Francis Dawson met and married a first wife Margaret Jane Paddock in Jersey. She was just 17 and they had two children before she died aged 20.

He then had had an illustrious career in the Navy and had ended up in New Zealand where he worked for the police and married a second wife Harriet Heywood Styles, a farmers daughter from Kent, UK. The family returned to live in the UK. And by the time Fanny was born her father was the portmaster at the New Dock, Llanelly, Wales. She was Harriet’s 8th child of 9.

By the age of 7 Fanny was living with her parents, one sister and her grandmother in Dartford Kent. By 16 she was living in Croydon with her parents and more of her siblings. Her father Gilbert describes himself as a retired Commander of the Royal navy at this point.

Fanny had two brothers Augustine and Sydney Dawson who married girls in Sri Lanka in 1873 and 1878. I imagine she may have gone to visit her brothers and met George in Sri Lanka.

She married George William Templer in Kegalle, Sri Lanka when she was 21. She had her first two children back in the UK. Ida was born in Kandy in 1879.

Fanny did return to England to have twins, George Dawson and Henry Buller, but most of the rest of the children (including a second set of twins) were born in Sri Lanka. The couple went on to have nine children.

George and Fanny retired back to the UK initially to the London area. By 1891 Fanny and her husband and four daughters are living in Dartmouth, Devon. They have servants at this point so they seem to be comfortably off at this point despite some earlier financial worries.

Fanny predeceased her husband by a few years.

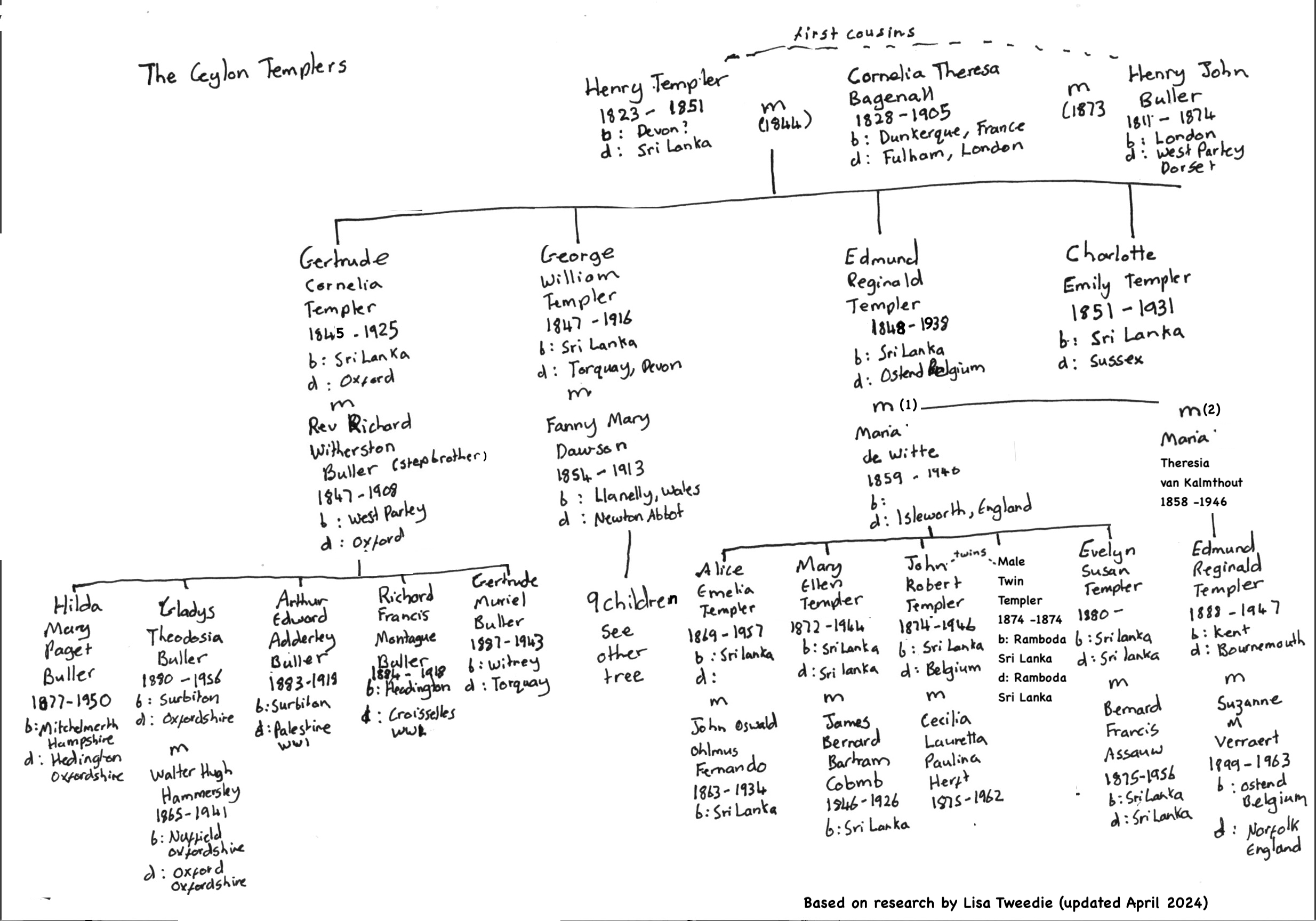

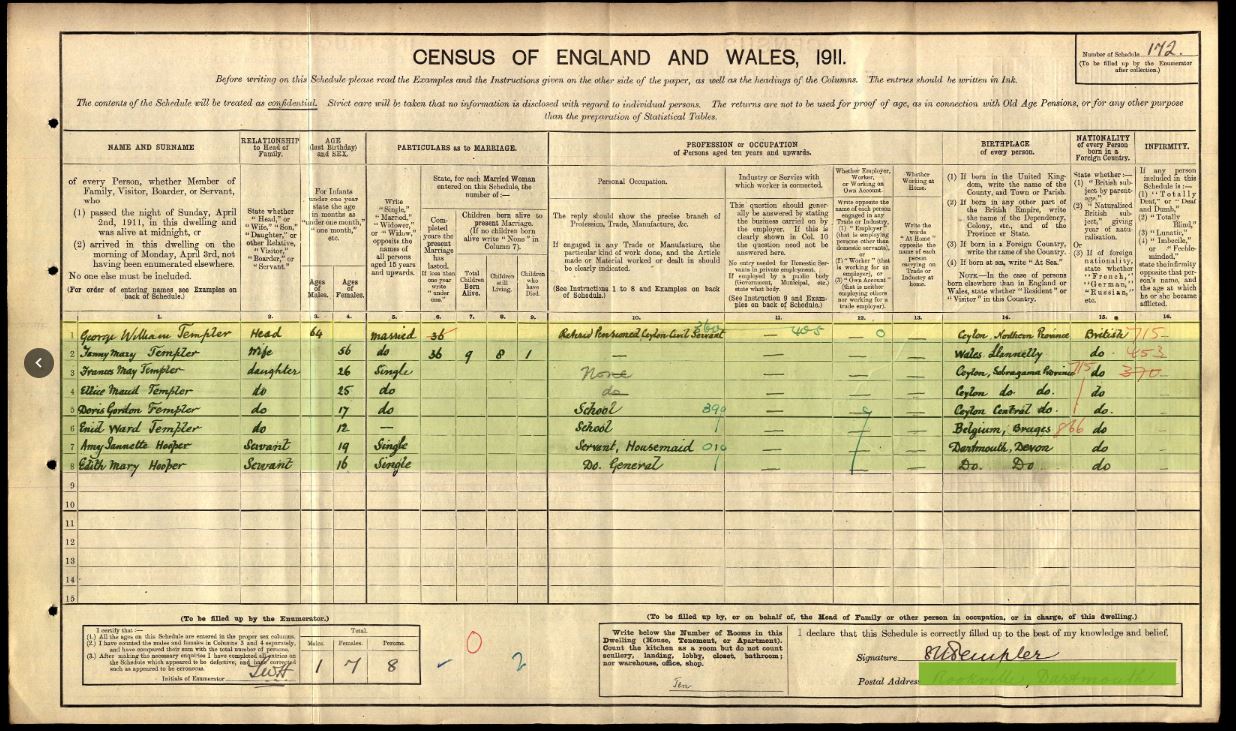

George William Templer

Born: 7 Jan 1847

Jaffna, North Eastern Sri Lanka, Sri Lanka

Died: 6 Jan 1916

Torquay, Devon, England

George William Templer was born in Sri Lanka. His father Henry Templer came to Sri Lanka aged 16 and worked in the Ceylon Civil Service in various roles until his untimely death aged 28.

His mother was Corneila Theresa Bagenall who was half Spanish (Basque) and half Irish. Cornelia had been orphaned in Sri Lanka.

Sadly Henry died when George was only 4. George had 3 siblings. One of which Charlotte died in her twenties. His sister Gertrude married their stepbrother Richard Buller. His brother Edmund Reginald married twice firstly Maria de Witt who was the adopted daughter of Proctor George Orloff of Badulla. They had five children together. One a twin died at birth. Descendents of this marriage lived in Sri Lanka until the 1970’s many are in Australia now. Edmund’s second marriage was to Maria Theresia van Kalmthout. They had one child another Edmund Reginald who became the British Vice Counsel to Belgium. Descendents of this marriage live in england.

Records show that Cornelia returned to live in Dunquerque where she had been brought up as a young child. When the children were old she moved to England and married her dead husband’s cousin Henry Buller.

Both George William and his brother Edmund returned to Sri Lanka.

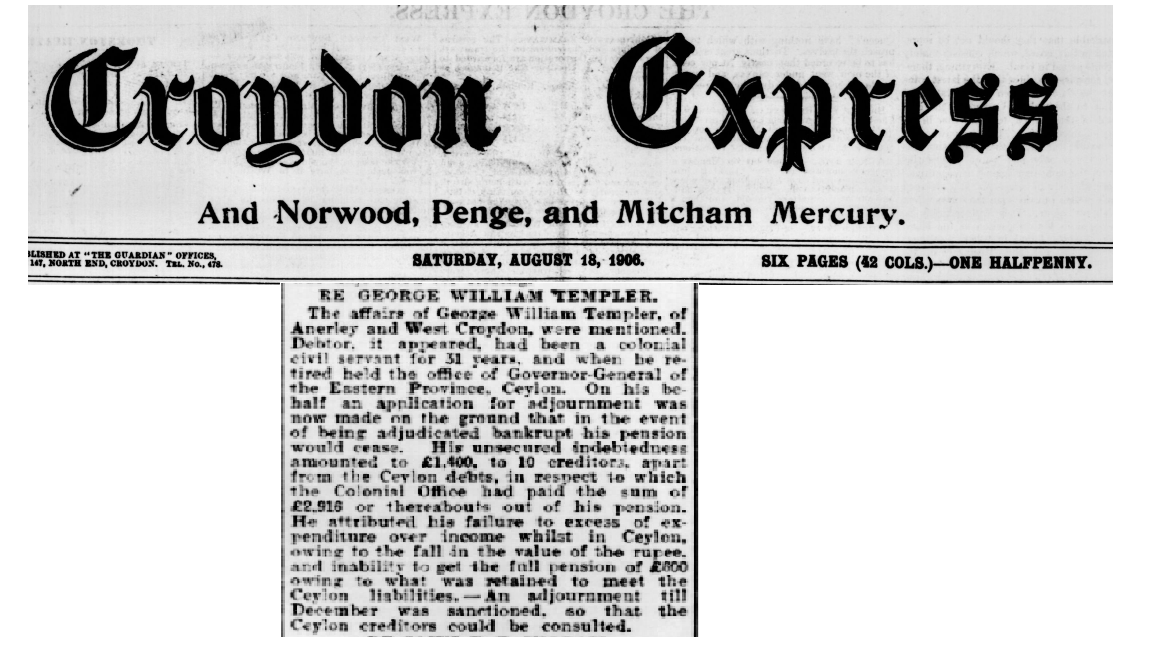

We know that George William married Fanny when he was 28 in Sri Lanka at that point he was already in the Civil service. A couple of years later he was in Sri Lanka working in the Civil Service. They had 10 children altogether and George gradually rose up the Civil service in various positions. Eventually retiring as Governor general of the Eastern Province in 1895.

At this point he left the Civil Service on the grounds of ill health.

George had retired to England by 1906 and seems to be living in Croydon and Anierley, South London. He was declared bankrupt due to problems with the exchange rate between the rupee and the pound according to his testimony .

George eventually settled in Devon and died there at the age of 68 a year after his wife had died. They are both buried at Teignmouth Cemetery.